17 Apr Hair Rituals Across the World

The cultural, social, and spiritual significance of hair extends far beyond its elementary biological function, framing it as a potent and multidimensional symbol within human societies. This layered significance penetrates multiple spheres of human life and interaction, rendering hair not simply a physical feature, but a canvas upon which societal values, norms, and narratives are articulated.

Viewed through a sociocultural lens, hair becomes more than a mere biological appendage. It evolves into a complex, symbolic tapestry that is deeply interwoven into the cultural fabric of societies worldwide. This tapestry is fashioned from, and reflective of, the collective beliefs, traditions, and practices of these societies, painting a vivid picture of their evolving identities (Synnott, 1987).

In the context of personal identity, hair operates as a powerful emblem, offering a visible statement of one’s selfhood, beliefs, and affiliations. It is an external representation of our internal selves, communicating our individual narratives to the world. However, the manifestation of these narratives is not free from the influence of societal norms and expectations, thereby intertwining individual identities with communal values.

Hair also acts as a critical signifier of gender, status, and power within societies. Its length, style, and adornments, regulated by societal norms, often demarcate gender roles and expectations, effectively embodying the societal construct of femininity and masculinity (Weitz, 2001). Moreover, hair becomes a badge of social status and power, with specific hairstyles often reserved for certain ranks or positions within societies, creating a visual hierarchy that reflects underlying social structures.

Hair’s role in shaping cultural, religious, and social narratives is not a one-way street. Just as it is shaped by these narratives, it also shapes them in return, offering a powerful tool for challenging, reinforcing, or transforming societal norms and values. This dynamic interplay positions hair at the heart of societal evolution, making it a mirror that reflects the cultural shifts and transformations within societies.

Thus, the importance of hair within human societies cannot be overstated. It is a potent emblem of identity, a visual marker of societal values, and a dynamic participant in the shaping and reshaping of societal narratives. This rich, multidimensional significance situates hair as a profound sociocultural symbol, warranting deep exploration and understanding.

Across diverse cultures, hair serves as a highly visible and public expression of personal identity. It is an external reflection of an individual’s internal self-conception, often manipulated and presented in a manner that communicates personal beliefs, affiliations, and societal standing. More than a biological feature, the styling, grooming, and presentation of hair becomes a dynamic canvas upon which individuals paint their identities in relation to societal expectations and norms (Weitz, 2001).

The grooming and presentation of hair are invariably entwined with the socially constructed ideals of beauty, masculinity, femininity, and status. These ideals differ vastly across societies, reflecting their unique cultural norms, values, and historical contexts. As such, the meaning imbued in specific hairstyles can range from signifiers of social status to markers of gender or expressions of personal aesthetics, thereby contributing to the identity of the individual within their societal context (Kaiser, 2012).

An illustration of this cultural significance can be seen amongst the Maasai warriors of Kenya. Hair for the Maasai is not simply a feature to be maintained but becomes a medium through which narratives of bravery, strength, and maturity are told. Their elaborate hairdressing, involving the application of red ochre and fat, is not just a testament to their personal grooming but serves as an emblem of their courage and a visual indicator of their transition into warriorhood (Hodges, 2014).

Moreover, the sociocultural narrative told through hair is not only personal but also communal. Hair, in its role as a public statement of personal identity, often serves as a visual encapsulation of the collective identity of a group or society. It stands as a symbol of shared experiences, beliefs, and values, strengthening communal bonds and fostering a sense of belonging and cohesion within societies.

Hair, through its styling, grooming, and presentation, is a powerful sociocultural symbol, enabling individuals to express their personal identities, conform to or challenge societal norms, and participate in the collective narrative of their communities.

The role of hair in delineating cultural, religious, and social narratives is dynamic and reciprocal. Hair is not simply a passive receiver of societal norms and expectations; rather, it functions as an active medium through which these norms are redefined, negotiated, and contested. This bidirectional relationship between hair and societal narratives underscores its instrumental role in the broader discourse of societal evolution (Synnott, 1987).

Shaped by cultural and social narratives, hair carries the weight of societal expectations and norms. These narratives, formed through historical contexts and collective beliefs, set the parameters for what is deemed acceptable or desirable in terms of hair presentation. From the conventional femininity associated with long hair to the masculinity signified by short hair, these narratives attach symbolic meanings to different hair attributes and styles, embedding them within the collective consciousness of societies (Weitz, 2001).

However, while hair assimilates these societal narratives, it also has the capacity to alter them. As a visible and mutable aspect of personal appearance, hair offers a potent platform for individuals to challenge or reinforce societal norms and expectations. This act of defiance or compliance, played out on the stage of hair, can provoke societal dialogue and trigger shifts in societal attitudes. For example, the natural hair movement that emerged among African American communities in the 1960s and has since gained global momentum, is a powerful demonstration of how hair can challenge racial stereotypes and catalyse social change (Lester, 2000).

In the dynamic interplay between hair and societal narratives, hair emerges as a barometer of societal evolution. As cultural and societal contexts evolve, so do the narratives attached to hair, reflecting changing norms, values, and attitudes. Hair, in its capacity to reflect and effect change, provides a mirror to the cultural shifts and transformations within societies, illuminating the ever-evolving landscape of human interaction and societal development.

In essence, the dynamic relationship between hair and societal narratives positions hair at the nexus of cultural, religious, and social discourses. By oscillating between conformity and defiance, between embodying and challenging societal narratives, hair plays a vital role in the evolution and transformation of societies.

Hair has played a central role in the cultural rituals of societies around the globe. Here are some notable examples:

1. Tonsure (Various cultures, especially religious): Tonsure is the practice of shaving the head or part of the head. It’s found in many religions, including Christianity (particularly in Catholic and Orthodox monastic orders), Buddhism, and Hinduism. In Hinduism, the ritual of Mundan involves shaving a baby’s head to cleanse the child from past life negativity.

2. Native American Long Hair Tradition (North America): For many Native American tribes, hair holds spiritual significance and is seen as an extension of the self. The cutting of hair by Native Americans is often done as a sign of mourning.

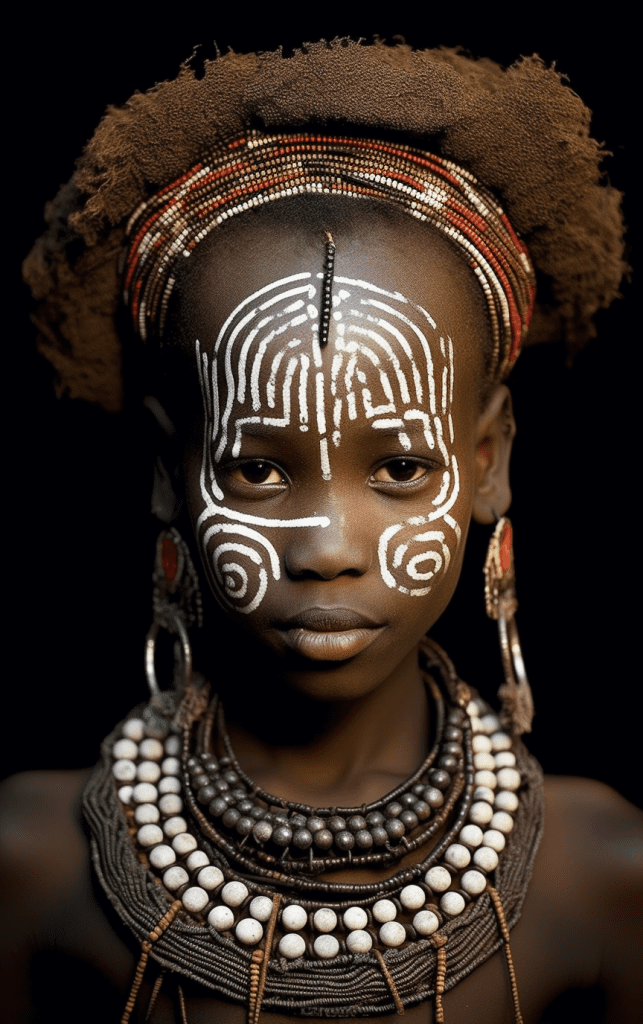

3. Rite of Passage (Africa): Among certain African tribes, hair cutting ceremonies are a common rite of passage. For example, in the Maasai tribe in Kenya and Tanzania, boys who are transitioning to young warriors, or Morans, have their heads shaved, marking a new phase in their life.

4. Red Hair Festival (Netherlands): In the city of Breda in the Netherlands, a festival is held annually in celebration of red hair. This unique event, which is a relatively modern creation, draws people from around the world to celebrate the rarity of red hair.

5. Hair Suspension Ritual (India): Among the followers of the Hindu deity, Lord Murugan, Kavadi Attam is a ritual of penance where some devotees suspend their bodies in the air by hooks pierced into their skin, including the skin on their backs and sometimes scalps.

6. Victorian Hair Art (United Kingdom): In the Victorian era, hair was often used in jewellery and art, particularly in mourning pieces. This practice was a way to remember and honor the dead.

The Victorian era, roughly spanning 1837 to 1901, witnessed a surge in the popularity of sentimental and mourning jewellery made of human hair, a material imbued with significant emotional and symbolic resonance. This research essay explores the socio-cultural factors influencing this practice, the craftsmanship involved, and the enduring legacy of Victorian hairwork.

**Hairwork as a Societal Norm in the Victorian Era

The Victorian era was characterised by complex rituals surrounding death and mourning, significantly influenced by the monarch, Queen Victoria, who herself mourned the death of her husband, Prince Albert, for four decades (Warner, 2008). As an extension of these mourning customs, the practice of crafting hairwork gained prominence. Hair, being a part of the human body that does not decay postmortem, offered a lasting physical connection to the deceased. This tangible remnant of the departed individual served as both a tribute and a reminder of mortality, encapsulating the Victorian fascination with death and sentimentality (Hallam, Hockey, & Howarth, 1999).

**Techniques and Applications of Hairwork

Victorian hairwork was a meticulous craft requiring significant skill. Hair was carefully cleaned, sorted by colour and thickness, and then woven or braided into intricate designs (Bell, 2014). These pieces were incorporated into various forms of jewellery, including brooches, bracelets, rings, and lockets, and also used in household items like picture frames and wreaths. In a cultural context, exchanging hairwork pieces within families or between friends was common practice, signifying bonds of affection, friendship, or romantic love (Koszmary, 2010).

**Legacy of Victorian Hairwork

Although the popularity of hairwork has significantly diminished, the tradition is not entirely extinct. Some modern artists continue to explore this medium, and Victorian hairwork pieces are regarded as valuable antiques, indicating the endurance of this art form within historical and cultural discourses (Mueller, 1995).

7. Sikhism (India): Sikhs believe in maintaining the natural state of the body, and this includes not cutting one’s hair. This practice, known as Kesh, is one of the Five Ks, or five articles of faith, that baptized Sikhs are expected to adhere to.

References

Kaiser, S.B., 2012. Fashion and Cultural Studies. London: Bloomsbury.

Lester, N., 2000. ‘Nappy Edges and Goldy Locks: African-American Daughters and the Politics of Hair’, *The Lion and the Unicorn*, 24(2), pp. 201–224.

Hodges, M., 2014. ‘The Secret Language of Hair’, CNN Style, 15 July [online]. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2014/07/14/world/africa/the-secret-language-of-hair/index.html

Synnott, A., 1987. ‘Shame and Glory: A Sociology of Hair’, *The British Journal of Sociology*, 38(3), pp. 381–413.

Weitz, R., 2001. ‘Women and Their Hair: Seeking Power through Resistance and Accommodation’, Gender & Society, 15(5), pp. 667–686.

No Comments