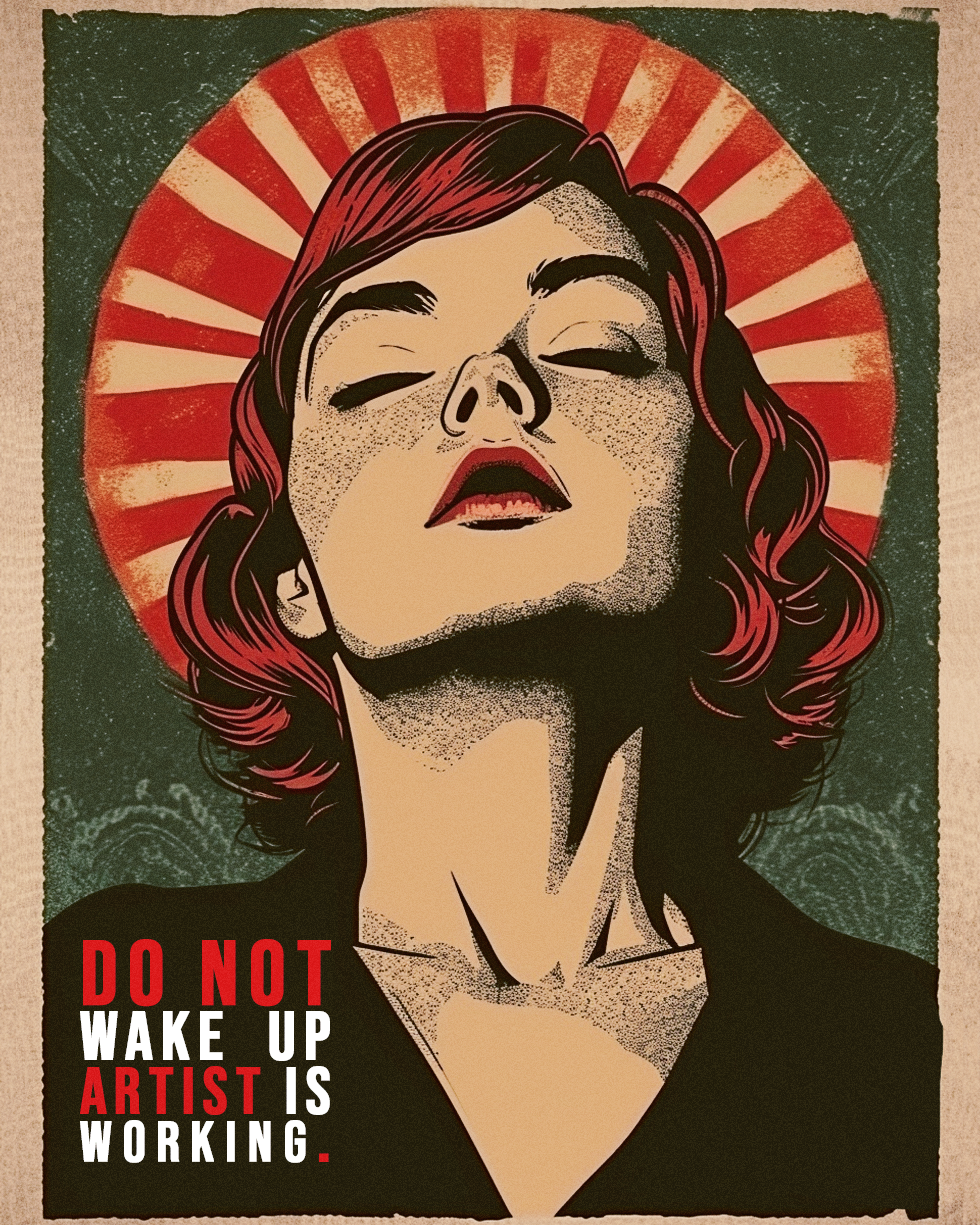

07 Dec Do not disturb, the artist is working

To become interested in sleep, it is enough to realize its importance in human life. The activity of sleep, commonly known as dreaming, is a necessity that constitutes approximately one third of our existence. Without this cyclical pause, we would not be able to function physiologically. Sleep brings rest from waking activity, switches the brain and the entire body to reset, regulating all its necessary life functions. It frees you from the automatism of actions and the routine of everyday life, and connects you to Mother Nature. And above all, it provides us with the opportunity to experience moments of direct contact with our imagination, free from all prohibitions and limitations.

In the face of the wealth of dreams, we wake up amazed (delighted, stunned, resentful, deeply moved, shocked, terrified, etc.) by their content and incredible course. What’s the point if the numerous duties that await us while we’re awake immediately push the dream away into non-existence as an event irrelevant to everyday matters?

Millions of dreams are lost every day without receiving the attention they deserve from their authors. Only a few people, as Jean-Paul (Johann Paul Friedrich Richter) and Paul Verlaine are said to have done, can write on their bedroom door: Do not wake up, the poet is working.

Why do we want to discover the meaning of our own and other people’s dreams? And why not? Psychologists and psychoanalysts agree that it is neither easy nor entirely certain in terms of the expected unambiguity of the found interpretation key. Sometimes it just doesn’t work out, and the dream vision soon disappears forever, leaving it completely unexplained. This applies not only to poetic dreams, which occur extremely rarely in our inner life, but also to those, so to speak, “standard” and prosaic ones, which due to their frequency and repetition (there can be no question of any routine here). constitute the absolute majority of our dreamlike activity. But the latter also sometimes contain an intriguing mystery.

The prosaic dream I am about to tell will have an explanation. Well, one day, late in the evening, I fell asleep knowing that early the next morning I had to go buy kefir, which I have liked since childhood and drink often. Buying a few liters of kefir in a plastic bag is part of everyday life. Nothing unusual or extraordinary. But this time it was true, because for a long time I had been suffering from severe pain: my foot hurt very much, especially the heel, which made walking very difficult and caused sharp pain with every step.

A real task, which needed to be undertaken the next day but was difficult to complete, turned into an unreal fantasy at night. Until I finally woke up from my sleep. I remembered the image that stayed in front of me and inside me for some time. High above my upturned head was a starry firmament with the Milky Way clearly visible on it. Where did it come from? Why did she suddenly appear in my dream? And why did she become so important in it? These are the questions we will now have to look for answers to.

We have three closely related elements here: text, context and constitution. Very specifically, but indirectly, which is worth remembering, the dream described here refers to them

and uses all three for its own purposes, encrypting its meaning. In composing dreams that take place in the psyche, psychoanalysts primarily noticed the role of symbols. I’m not saying it’s wrong or wrong; I do not deny the validity of this method of explaining dreams. What I’m saying is that a similar approach, if it is Freudian and solely focused on this one key, is not enough.

In the process of symbolic encoding of a dream message, in addition to symbols, various other semantic tropes and expressive means – a whole range of them – participate as important realities, which will be discussed many times in this thesis.

Above all, however, in the course of the dream itself, and then in its disclosure through description, the mediation of narrative makes itself felt each time. The narrative in the dream, just like the narrative surrounding the dream after waking up, turns out to be an indispensable factor during the dream: a sine qua non.Š The dream tells, the dream presents, the dream presents. What is interesting and worth emphasizing: narrative as a necessary and inalienable process appears – not only in dreams, but also after the fact, when we reconstruct what we dreamed, recalling the dream in memory and telling it to someone else. But how much confidence can we have in a dream report given after the fact? The answer is simple: trust is necessarily limited. Sigmund Freud says this:

“the scope of waking dreams is extremely diminished in comparison with the rich material that gave rise to them.”

And adds:

The elaboration of a dream is therefore essentially a case of the unconscious elaboration of subconscious thought processes. Let’s go back to history: decorationThose who invade a country do not act there according to the law they find there, but according to their own law. However, it is obvious that the result of development and dreams. sleep is a compromise. In the distortion imposed on the unconscious material and in the often insufficient attempts to give the whole a form still acceptable to the ego (secondary elaboration), one can recognize the influence of the not yet paralyzed ego organization.

However, there is no other way of knowing. There is no dream without the participation of a oneiric narrative and there is no story about what it was like, how it developed, what was in it, what was not there, what we dreamed of, what it presented and said – without activating the intermediary mode of narrative, essentially its secondary, i.e. retroactive and reconstructive. In fact, whenever we talk about what we dreamed, we become (re)constructors of a story that is a report, a subjective account of something past. When we try to analyze and interpret a dream, we tend to be its deconstructors, operating the scalpel of memory in the extremely delicate, subtle, non-obvious and fleeting tissue of the oneiric text. Let us return to the described dream. Going for kefir – going, not buying, I emphasize – meant a triple burden of duty: getting up early in the morning, traveling a considerable distance to the market where “my” dairy stand is located, and then returning home with a bag of several kilograms.· I didn’t have car, I had to become a transport vehicle myself. The distance between my place of residence and the market would normally not be a problem if it were not for the sharp pain in my foot with every step.

I knew I had to defeat him, and my knowledge came from recording the pain that had been haunting me for many days. The reader will no doubt have noticed that I have used the word “mine” three times in this paragraph, with no doubt intended to identify the dreamer with his own dream…

Why the Milky Way? Firstly, I think it expressed a great distance in the terms of a sidereal hyperbole (and with it the distance to cover that awaited me the next day). Secondly, the “milk” name of this astronomical phenomenon evoked synecdoche associations with kefir itself, which was absolutely absent in my dream. Thirdly, there was a sense of unattainability of the purchased goods in this image. The type of kefir I like the most wasn’t always available in my area. He appeared at the fair stand at dawn, occasionally in small numbers, disappearing quickly as the day progressed. In this situation, the early morning expedition became both a duty and an inconvenient task that had to be undertaken and fulfilled.

This is how the reality of what awaits me, arising from desire, received its metaphorical expression during the dream. If you try to place it among different categories

dreams, it would probably be a standard “task” dream of the type: something to do. Its course presented in the above description boils down in this case to coping with the challenge waiting for the next day. Everything that is important is recorded in it: image-text, context , from which my mind drew the methomimic material of the dream itself, and the milky constitution described above to which it referred.

The dream is there – the dream disappears. It begins, makes us dream, lasts until we wake up, then dissipates and disappears. Its ephemeral nature is characterized by such a degree of hazy airiness of immaterial dream matter that it seems to be a text without a text. And in fact it is something like that. This greatly complicates the status of the subject of our inquiry. He was there, he barely existed and he’s gone. He disappeared like a fleeting, disembodied phantom. It remains unavailable henceforth. We do not study dreams as such, but their narrative and linguistic emanations, which allow us to get closer to the oneiric spectacle completed and recorded only in someone’s fleeting memory.

The thing about a oneiric spectacle is that it appears in our lives, and soon after waking up (read: the transition of consciousness to the waking state), it disappears into oblivion. It’s hard to say how much we lose from a dream when it ends. Certainly a lot. Whenever you try to capture it and present it in a way that is accessible to you, you inadvertently simplify it. Each retelling of a dream inevitably involves a choice and a selective reconstruction – and therefore a loss one way or another.

What is more important is what remains in our consciousness despite everything. This is where the process of (self-)cognition takes place. The process is limited, incomplete and full of defects of unreliable memory. But this loss should not paralyze us and discourage us from studying the phenomenon itself. If we compare a dream with a kind of daydream, such as experiencing a theater performance or a cinema screening, then what remains in the viewer’s memory is a very small percentage of what he or she absorbed with a sense of one hundred percent participation.

Does this mean that sleep as a subject of scientific investigation de facto does not exist and that you are in research?

Are we doomed to only indirect testimonies about him? Not exactly. Materially (textually), yes, it does not exist. It disappeared upon awakening, but remained a living memory recorded in the dreamer’s mind. No one will deny that a given dream is a phenomenon. occurred in certain circumstances,

time and place. That it was there, that it happened to someone and that they dreamed about it. That it had a beginning, a development and an end. That specific characters, objects, activities, reactions and events appeared in it. And that, therefore, it can be treated not as an absolutely absurd event, a manifestation of total chaos and incoherent gibberish of a distracted psyche, but as a meaningful message.

The specificity of a dream vision lies, among other things, in its fleeting and transient status as a oneiric sign. It was there, it happened a moment ago or a long time ago, but it is not there and will never be in this dream shape again. Therefore, does semiology, as an interdisciplinary field of science by its nature – in view of this insurmountable, impossible to remove and repair, inaccessibility of the original text – have any right to know dreams?

In an interview conducted over half a century ago by Krystyna Pomorska, Roman Jakobson reflected on the issue of the scope of semiotic research, appropriate

the boundaries of the emerging science and the types of signs that fall within the scope of interest of semiotics, he formulated the following answer – by definition open and non-doctrinal:

[. ..] If semiotics, as the etymology of the word suggests, is the science of signs, no signs are subject to ostracism, and if the diversity of sign systems reveals systems that differ from others in their own specific features, then this series can be distinguished as a separate class, remaining nevertheless within the limits of the general science of signs.

Whenever we tell what we dreamed, the natural act of dreaming, accessible to everyone, gains its own cultural expression. What is natural discovers its symbolic meaning and at the same moment it becomes not only a product of nature, but a cultural phenomenon. The dream passes, but its cultural echo continues. Sometimes it lasts for centuries. Cultural adaptation of the dream is taking place in the history of human culture

continuously since ancient times (Gilgamesh, the pharaohs, Nebuchadnezzar, Greek myths, the Delphic oracle, the Aeneid, the Odyssey, the tales of One Thousand and One Nights, the famous mane tekel Fares on the wall of the Babylonian palace during the feast given by Belshazzar, a collection of prophetic dreams of the Old and New Testament, etc. 😉 and it seems to have no end.

Drawing wisdom and creative inspiration from dreams is a not often appreciated aspect of the history of the evolution of the species homo sapiens or – if you prefer – homo somnians.

Carl Gustav Jung was the one who saw in the dreaming process its eternity written in an ancient, but still living, symbolic language. Symbolic language fascinated his teacher, Sigmund Freud, who studied Hamlet and closely looked at Dalí’s paintings. Jung also did the same, seeing an analogy with dreams in artistic activities. Science in both of them intertwines and constantly meets with art. The boundaries of these fields are deliberately abolished. As in the past, it is still worth drawing cognitive energy from that important alliance of scientists and artists.

The socio-cultural translation of dreams, their disclosure and explanation, takes place through art and its multiple languages: drawing, painting, sculpture, architecture, garden art, music, dance, theater, comics, cinema, computer graphics. Each era, each period of the development of civilization and artistic culture, has and applies its own keys and preferences in this respect. In the early 18th century, Joseph Addison noticed a striking analogy between a dream and a play, suggesting that the human soul, released from the body during sleep, becomes at once the theater, the audience and the actors.

We will return to this thread, which has lost none of its relevance and relevance despite the passage of two hundred years. One of the great concepts regarding the role of dreams in culture and their broader meaning for all humanity is the memorable thought of Jorge Luis Borges. This enthusiast of the products of oneiric imagination, an erudite and an experienced collector of dreams, referring to Addison’s metaphor, in the preface to the completed in the fall of 1975

Dream Books wrote:

A literal reading of Addison’s metaphor would lead to the dangerously appealing thesis that dreams are the oldest and most complex literary genre. It does not cost us anything to accept it for the purposes of the Prologue and reading the texts contained in this book; it would justify addressing the universal history of dreams and its impact on the humanities.

I would like to add that the dream is not only the oldest literary genre, but also a cinematic one, as evidenced by the captivatingly beautiful – one might say surreal – recordings of the movements of animals and people made in the 1980s.

19th century by Eadweard Muybridge, as well as – created long before the films of the Lumiere brothers – pantomimes lumineuses: pioneering animations by Emile Reynaud (1892). After this short historical digression, let us return to the main topic of our considerations, concerning the natural and cultural properties of sleep.

If culture, as Sigmund Freud believed, derives the sense of its functioning from the existence of prohibitions and orders, then our dreams and the freedom to dream whatever we want are at the forefront of the eternal struggle between what is allowed and what is forbidden. and forbidden. Sleep frees the mind. It does not forbid anything to man, the ria allows everything, triggering and irresistibly pushing forward the stream of images in the wild. However, not every dream makes us feel free. It depends on certain circumstances of our lives. Dreams are not random in this respect. the sense that they always occur in specific circumstances that concern us. In relation to a dream, we call the consituation the register of one’s own experiences stored in the dreamer’s memory. This imaginative record always refers to specific realities. The time distance is not important, what matters is the return of a personal experience activated at a given moment, which does not give peace to the dreamer’s psyche, does not allow itself to be forgotten and demands an outlet in our inner life in the form of disclosure.

The situation accompanying dreams determines, to a large extent, their course and character. Under the rule of tyrants and dictators, the dream is completely different. We live in such and no other circumstances, and therefore we also dream, deprived of the right to choose and enslaved by the coercion of what is imposed by force by the authorities. A man enslaved and subjected to permanent violence finally begins to dream. The difference between an authoritarian regime and a democracy in the context of dreams? In authoritarianism, people dream about what is ordered or forbidden, in liberal democracy (and this is the great privilege of life guaranteed by it) – about whatever they want.

A prime example of a dream, or rather a nightmare, under conditions of totalitarian pressure on the individual is the mother’s anxious nightmare in The Mirror (1978) by Andrei Tarkovsky. During this dream filled with horror, the newspaper’s proofreader’s terrible fear is revealed that she has let an error into print, for which she will pay with terrible repression from the authorities. The oppressive system destroys peace and annihilates the freedom of dream images. The dreamer then dreams about what threatens him or her on a daily basis.

Even under despots, however, there are exceptions from time to time. Nevertheless, in a dream, a person is a free individual. Josif Brodsky comes to mind with his equally bitter and penetrating thought that a man is better off in the most imperfect democracy than even in the greatest splendors of tyranny. An excellent illustration of this desire for freedom, as discussed here, is provided by two Russian animated films dedicated to Brodsky by Andrei Khrzhanovsky: A Cat and a Half (2003) and A Room and a Half (2009) – both based on the narrative devices of oneiric cinema ~ Especially the one appearing in the latter of these films, a phenomenal sequence of an escape dream of a first-grader expelled from school, who, in panic, tries to escape through a dreamlike city from Lenin, who is chasing him and panting for revenge on a defenseless boy.

No Comments