28 May Conclusions

During my latest solo exhibition, a critic asked a question that would lead me on a journey of exploration and discovery.

‘Why the strong emphasis on hair?’ This question stirred my curiosity, making me realise that my intuitive focus on hair needed to be understood deeper… Intrigued by the question, I decided to embark on a journey- a deep dive into the symbolism and socio-cultural significance of hair.

To assist me in this exploration, I partnered with philosopher and curator, Mrs. Dagmara Giej. We began by researching historical documents, art, folklore, and ancient texts, immersing ourselves in the rich tapestry of hair symbolism and its cultural meaning.

We focused our research on Europe, and Slavic cultures, however those themes are similar in many countries across the globe. Hair has always held a profound significance in human societies.

Its symbolism permeates various facets of culture and spirituality. It is a story that has been woven through the tapestry of human history. Throughout history hair has been an important aspect of personal identity, often linked with social status, gender, religion, and cultural heritage.

Historically, hair has been a potent symbol of femininity, reflecting women’s connection to their ancestry and traditions. In numerous cultures, the act of braiding or styling hair has been a tradition passed down through generations, solidifying the bond between mothers and daughters.

Elizabeth Barber, explores the social and cultural significance of women’s hair throughout history, demonstrating the intimate connection between hair and female identity.

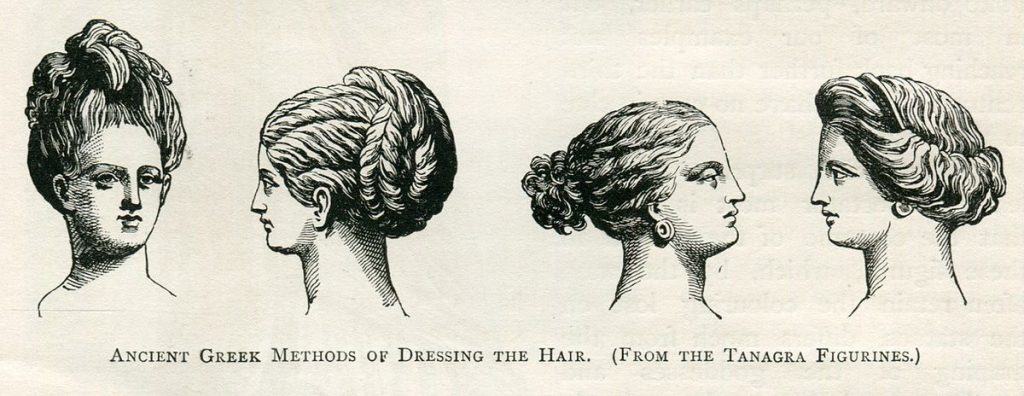

In ancient Greece, women’s hairstyles were considered an essential aspect of their identity and status. Women would often adorn their hair with intricate hairstyles and accessories, symbolising their wealth and social standing.

In the Victorian era, hair was imbued with sentimental value, with hair jewellery becoming a popular way to memorialise loved ones who passed away. Hair was viewed as an intimate part of the individual, serving as a connection between the living and the dead.

The exploration of hair’s symbolism in mythology and its connection to femininity and cultural heritage highlights the stories and meanings rooted within this everyday element.

Hair Representing feminine strength, identity, and heritage echoes through various mythologies and rituals. By examining them we can better appreciate the connections between mythology, culture, and individual expression.

Hair serves as extension of selfhood and carries profound symbolic weight across cultures.

Regarded as an integral part of identity, femininity, strength and status, hair becomes an object of intricate interplay between personal and societal constructs.

The manipulation and removal of hair is still a striking expression of power dynamics, often employed as a tool for humiliation, punishment, and control if done forcefully, or a powerful statement and act of rebellion. As this embodiment of the personal meets the political, hair emerges as a battleground of conflicts and discourses that resonate deeply in cultural history.

Our research further underscored hair’s role as a battleground where personal and societal constructs intersected. The act of forcible hair removal, specifically, has been a powerful tool of female subjugation and disempowerment, often manifesting as a form of punishment and control (Witoszek, 2021; Sarasua, 2018; Bettie, 2014). This act of shaving transcends physicality, instead representing an intrusion into a woman’s autonomy, leading to the severance of communal ties and selfhood perception.

Tracing back to ancient Rome, the practice of punitive hair shaving served as a public disgrace marker, effectively alienating women from societal honour and virtue norms (Dixon, 2001). This act represented societal mechanisms of control and regulation, extending into the societal image and identity of women (Barker, 2015).

This practice continued through the Medieval and Early Modern periods in Europe, appearing strikingly during the witch trials (Levack, 2016). Hair shaving, thought to expel evil spirits harboured within a woman’s hair (Gijswijt-Hofstra, 2000; Robisheaux, 2009). Furthermore, it served as a de-feminising and dehumanising process, reinforcing the accused women’s portrayal as demonic entities and bolstering societal justification for their punishment (Kramer & Sprenger, 2001; Roper, 2004).

In the aftermath of World War II, hair shaving evolved as a method of public shaming for women accused of collaborating with enemy forces, symbolising collective catharsis in war-devastated societies (Virgili, 2002; Szejnmann, 2018; Duchen, 1997). The women accused, represented as symbols of national betrayal, had their femininity erased, with hair removal reinforcing the societal need for scapegoats and the gendered power dynamics (Sebba, 2016).

The forceful removal of hair is a recurring practice symbolising female disempowerment and control. It transcends the physical to infringe on a woman’s autonomy and self-perception.

In a powerful twist of symbolism, shaving one’s hair can also be seen as a deliberate act of rebellion. Women, who are often subjected to societal expectations of maintaining their hair in certain ways, might shave their hair as an act that serves as a powerful statement of autonomy, resistance, and non-conformity. This act could be interpreted as a refusal to adhere to traditional standards of femininity and beauty, a rejection of the gendered power dynamics embedded in hair symbolism, or an assertion of personal freedom.

During the Hundred Years’ War, Joan of Arc defied societal norms by cutting her hair short and dressing in male military attire. This act was not only practical for a woman leading an army, but it was also a radical statement of defiance against the gender norms of her time. Joan’s hair was a tangible symbol of her rebellion against societal expectations, her assertiveness, and her dedication to her divine mission.

In modern times celebrities have used hair shaving as a form of rebellion against norms and pressures. In these cases, the act of shaving one’s hair was not only a personal statement but also a public performance of resistance. Women shaving their heads became a challenge to the beauty norms and assert their autonomy over their bodies.

Following the broader historical and cultural research, our investigation concentrated on Slavic traditions and perceptions concerning hair. Spanning Central and Eastern Europe, Slavic cultures offer a lot of hair-related customs and symbolic practices (Wilson, 2017)

In Slavic societies, hair has traditionally been perceived as a repository of ‘siła’, or vital force, and a marker of personal and spiritual wellbeing (Ryan, 2013). The care, styling, and presentation of hair have been intricately woven into various rituals and pivotal life events, thereby imbuing them with social and symbolic import (Pavlič, 2018).

The way a woman’s hair was maintained and displayed often served as a visual indicator of her marital status and moral integrity. Unmarried girls typically wore their hair in one braid, signifying their innocence and marriageability (Hunt, 2014). Upon entering matrimony, women adopted more intricate hairstyles or even covered their hair, signalling modesty and respectability (Habinc, 2000) Mothers usually had two braids, one for her own protection, and one for the child. Interestingly a woman who had their hair down and unbraided would be considered a witch.

The act of hair cutting in these cultures had significant symbolic connotations. Such practices were frequently associated with transformative life events, such as rites of passage, mourning rituals, or even signifiers of servitude or disgrace (Wilson, 2017). Instances of enforced hair cutting in punitive or humiliating contexts have also been echoed in Slavic societies, albeit accompanied by distinct cultural interpretations and ramifications (Kotar, 2018).

Hair rituals, traditions, and folk magic provided a window into the rich cultural legacy of Poland and other Slavic societies. Despite their antiquity, these practices remain deeply ingrained in Slavic cultures, bearing testament to the resilience of traditional beliefs and customs in the face of modernisation.

In addition to historical and cultural investigations, I also found great value in studying contemporary female artists who have chosen hair as a central theme in their work. This exploration helped me to understand the universality of hair symbolism across cultures and eras. Artists that I looked at (and that you can see on here on my blog) provided inspirational examples of how hair can be used as a powerful artistic medium to express a multitude of narratives.

Artists like Kaixuan Feng who used her own hair as a brush to create her paintings, challenged the traditional boundaries of art and demonstrated the potential for hair to be not just a symbol, but also a tool for artistic expression.

These diverse approaches not only enriched my understanding of hair symbolism but also provided me with new perspectives on how hair could be manipulated and represented in artistic forms.

This exploration of hair in contemporary art, coupled with my historical and cultural research, has imbued my work with a richer, more nuanced perspective. By incorporating these insights into my art, I aim to engage viewers in a deeper dialogue about the personal and societal significance of hair, opening new avenues of interpretation and understanding. This in-depth exploration significantly influenced my creative process and conceptualisation. The intersectionality of hair as a symbol of personal identity, power dynamics, and cultural heritage resonated deeply with me, instigating a transformative shift in my artistic approach.

Drawing upon historical narratives, cultural practices, and socio-political discourses, I sought to recontextualise these elements within the contemporary art scene. My artwork began to mirror the multifaceted symbolism of hair, incorporating aspects of femininity, heritage, power, and resistance.

As I delved deeper into the world of hair symbolism, my art became not just a form of personal expression, but a dialogue between history, culture, and the individual.

References

Barstow, A.L. (1994) Witchcraze, A New History of the European Witch Hunts. New York: Pandora.

Barker, E. (2015) ‘Hairstyles and Hairdressing in the Talmud’, Materia Judaica, 10(1), pp. 7-29.

Bechtel, G. (1997) La Sorcière et l’Occident. La destruction de la sorcellerie en Europe, des origines aux grands bûchers. Paris: Plon.

Bettie, J. (2014) Women Without Class: Girls, Race, and Identity. California: University of California Press.

Chollet, M. (2019) Czarownice. Niezwyciężona siła kobiet. Kraków: Karakter.

D’Eaubonne, F. (1999) Le Sexocide des sorcières. Paris: Editions Spengler.

Dixon, S. (2001) Reading Roman Women: Sources, Genres, and Real Life. London: Duckworth.

Federici, S. (2014) Caliban et la sorcière. Femmes, corps et accumulation primitive. Genève–Marseille: Éditions Divergences.

Gijswijt-Hofstra, M. (2000) ‘Witchcraft After the Witch-Trials’, in de Blécourt, W. & Davies, O. (eds.) Beyond the Witch Trials: Witchcraft and Magic in Enlightenment Europe. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Habinc, M. (2000) ‘Traditional Slovene weddings and wedding customs’, Traditiones, 29(2), pp. 123-138.

Hunt, A. (2014) ‘Symbolic hair in the Art of Medieval Europe’, Gender & History, 26(1), pp. 1-33.

Ivanits, L. (1989) Russian Folk Belief. New York: M.E. Sharpe.

Kotar, P. (2018) ‘Hair customs in Slovene folk tradition and in folk tradition of other Slavic nations’, Studia Mythologica Slavica, 21, p

p. 167-188.

Kramer, H. & Sprenger, J. (2001) The Malleus Maleficarum of Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications.

Levack, B.P. (2016) The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe. Abingdon: Routledge.

Pavlič, D. (2018) ‘Traditional Hair Arrangement in Slovenia’, Etnolog, 28, pp. 155-171.

Robisheaux, T. (2009) The Last Witch of Langenburg: Murder in a German Village. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Roper, L. (2004) Witch Craze: Terror and Fantasy in Baroque Germany. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Ryan, W.F. (2013) The Bathhouse at Midnight: An Historical Survey of Magic and Divination in Russia. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Sarasua, C. (2018) She-Devils, Harlots and Harridans in Early Modern Spain. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Wilson, A. (2017) ‘Hair and the construction of identity in early Slavic ecclesiastical culture’, Russian History, 44(1), pp. 1-19.

Witoszek, N. (2021) The Origins of the Regime of Goodness: Remapping the Cultural History of Norway. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

No Comments