13 Feb Formism – Polish Philosophy and art movement.

Formism (previously known as the Polish expressionism), was a modern art movement active in from 1917 to 1922, proclaiming a departure from Realism, and the solidification of the superiority of form over content.

Its beginnings were associated with exhibitions of independent artists organised by Zbigniew Pronaszko in Kraków.

Fashioned after the Parisian Salon des Independants, they were a response to the artistic dominance of the ‘Sztuka’ Society of Polish Artists and the exhibiting policy of the Society of Friends of Fine Arts, which expressed conservative views on art.

The first two shows, which took place in Kraków in 1911 and in 1912, featured Andrzej and Zbigniew Pronaszko and Tytusz Czyżewski, and also Xawery Dunikowski in the first one. As much as the first exhibition did not signal the idea of modernity in art yet, the second one announced the later explorations of the artists. It was followed by a solo exhibition of Tytusz Czyżewski’s works – apparently mentioned in his memoirs – which took place at the Palace of Arts in Kraków and was shut down after a week due to controversy caused by the innovative paintings presented within. The third Exhibition of Independent Artists took place in Kraków in 1913, at the Spiski Palace. Participating artists included the Pronaszko brothers, Tytus Czyżewski, Jacek Mierzejewski, and Eugeniusz Zak.

Ideological struggle with Realism

Works by young artists shown at the above mentioned exhibition showcased their explorations in the fields of cubism and expressionism, and by the same token marked a turning point in Polish art. From the start, they were accompanied by theoretical reflection, whose beginnings were marked by a programmatic paper written by Zbgniew Pronaszko titled prominently Przed Wielkim Jutrem (Before the Great Tomorrow). Published in 1914 on the pages of the Kraków-based magazine Rydwan, it was accompanied by a motto from Juliusz Słowacki’s Genezis z Ducha (Genesis from the Spirit):

Everything is created by the Spirit and for the Spirit, and nothing exists for a corporeal purpose.

Pronaszko entered in an ideological struggle with Realism, the concept of mimesis, and the requirement to copy nature in art. According to his beliefs, nature may only be a source of stimulation, inspiration for artists, whose task it is to create new forms. He criticised realists for treating nature as a model, and for merely offering an interpretation of it, which cannot be regarded as creativity. He thought that some things do not exist objectively in nature, but belong to a sphere of emotions, reflections, and impressions, to the realm of experience, which an artist should be able to express through his own means – in painting through colour and outline, in sculpture – through form and shape. In this magnificent essay rooted in Polish modernist tradition, Pronaszko pointed to the origins of expressionist art in the Romantic tradition, preceding the famous study by Przybyszewski, Ekspresjonizm- Słowacki i Genezis z Ducha (Expressionism: Słowacki and Genesis from the Spirit).

Polish Expressionists

In 1914, the collective activities of the artists and organisation of annual Exhibitions of Independent Artists were interrupted by the outbreak of World War One. They returned to those ideas in 1917, creating a new art group – the Polish Expressionists. The notion of expressionism in the group’s name refers to a broad array of meanings encompassing various artistic tendencies, such as Cubism or Futurism, which on one hand stands as a manifestation of antirealism and antinaturalism, and on the other – as a protest against Impressionism and Colourist inclinations. One of the group’s important practitioners and theoreticians was Leon Chwistek, who in 1919 regarded expressionism as a symbol of protest against the official art. Some artists, however, such as Zbigniew Pronaszko, were interested in the theory and visual forms of the art of emotions and expression, especially German expressionists. The programmatic isolation from Expressionism, which was also indicated by the change of name, took place in 1919.

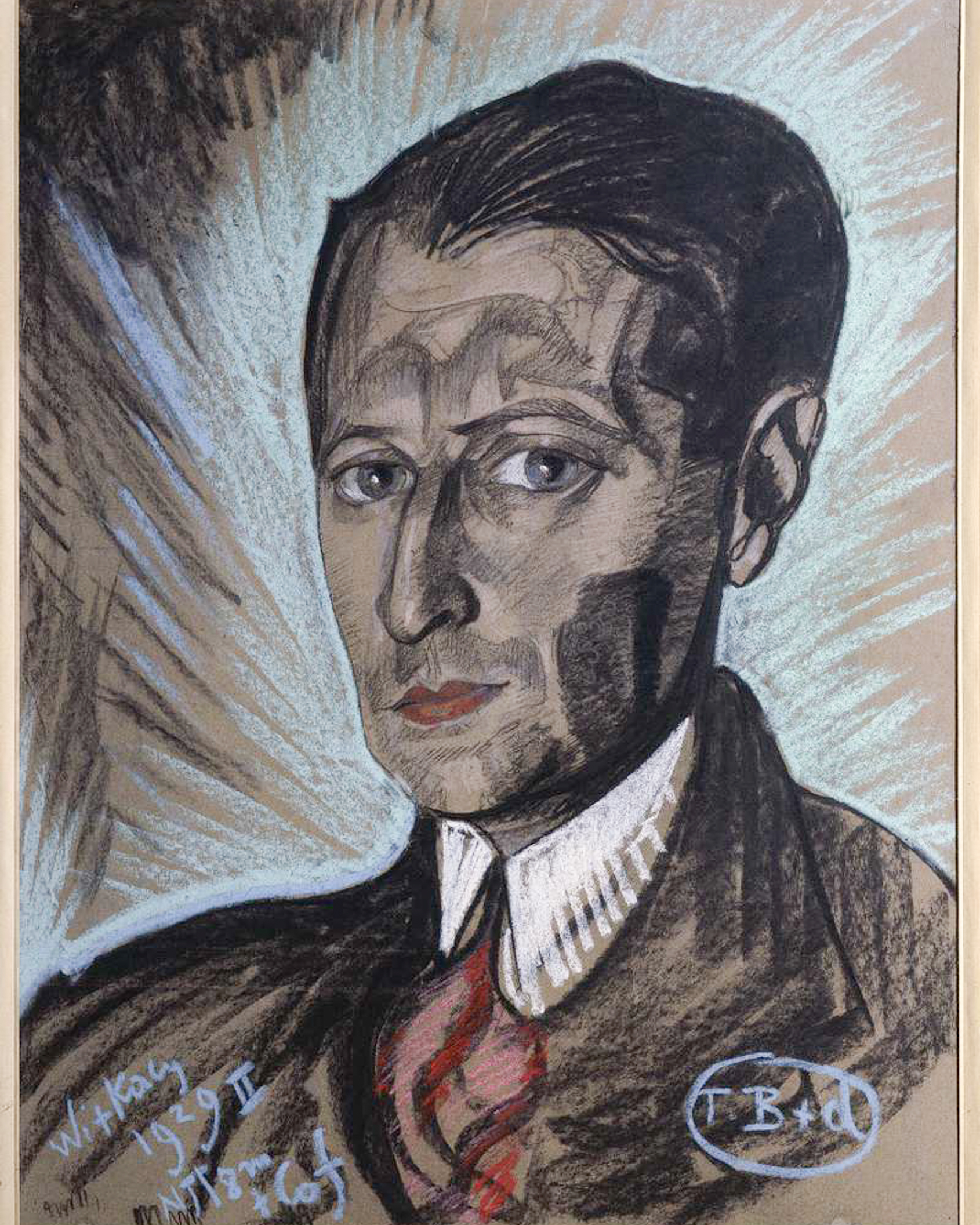

The first exhibition of the Polish Expressionists opened at the seat of the Society of Friends of Fine Arts in Kraków on 4th November, 1917. It was accompanied by a programmatic declaration in the form of quotations about the art of such authors as Adam Mickiewicz, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Paul Cézanne, Henri Matisse, Jean Metzinger, as well as a specially written essay by Zbigniew Pronaszko. The exhibition gathered eighteen artists, a few of which were permanently based abroad. It featured nearly one hundred works, including a collection of paintings on glass and steel engravings from the Podhale region. From the large group of participants surfaced a circle of the later Kraków Formists, actively creating and exhibiting, as well as promoting the ideas of new art. They included: Leon Chwistek – painter and theoretician, as well as a prominent philosopher and mathematician; Tytus Czyżewski, painter and poet, and an art critic; Zbigniew Pronaszko – painter, sculptor, and one of the key theoreticians of the movement; and painters: Henryk Gotlib, Jan Hrynkowski, Tymon Niesiołowski, and Andrzej Pronaszko. In the following years, the group was also joined by: Konrad Winkler, who was a painter, art critic, and the group’s historiographer; Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (Witkacy) – painter, writer, playwright, philosopher, and the group’s theoretician; August Zamoyski – sculptor, who also belonged to the Poznań-based expressionist group ‘Bunt.’

The mentioned text by Pronaszko accompanying the group’s first exhibition demonstrates significant differences from the 1914 essay. Form becomes the key issue tackled by the artist, while painting is described as a ‘return to painting,’ understood as the opposite of the return to nature. Tytus Czyżewski on the other hand, introduces the notions of ‘internal form’ and ‘external form’ in an article published in the following year. The external form is received through senses from the surrounding world, while the internal one is described as a ‘pure symbol of the overall form,’ which can be contained through ‘the power of creative vision.’ It proposes a creative, constructive approach towards the artists’ reality and recommends them to follow their instincts.

Even though in the artistic practice of the Expressionists one may find a variety of approaches and styles, they mostly shared their sources of inspiration, consisting mainly in the art of Cubists and Futurists. They shared a negation of Realism, the tradition of mimesis and illusion, but also a distance towards modernist concepts of symbolism, often tinged with mysticism. They also moved away from the decorative nature of the art of Young Poland. They aimed to create a Polish national style, based on a new definition of form and on new means of expression, but derived from from local traditions and roots, such as Podhale’s folk art or guild arts of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The group’s presentation met with a response from the public, which was largely outraged by the radical means of artistic expression. On the other hand, it also immediately gained a circle of supporters, artists, critics, and theoreticians of art, such as Jan Bołoz Antoniewicz, Tadeusz Sinko, Leon Schiller, Stanisław Mróz, and Stanisław Przybyszewski. Some of the strong opponents of the group’s actions included Karol Irzykowski, Władysław Prokesz, and Leon Piniński.

Polish Expressionists collaborated with other associations and artists implementing new art, such as for instance Futurist poets, including Bruno Jasieński, Stanisław Młodożeniec, Anatol Stern, and Aleksander Wat. They became close to the circle of the Kraków Futurist club Gałka Muszkatołowa, and were in touch with such publications as Maski or Wianki, where they published their drawings and texts – predominantly Zbigniew Pronaszko, Leon Chwistek, and Tytus Czyżewski. They also held an affinity with the ideological profile of the Poznań-based magazine Zdrój. They maintained contact with artists affiliated with Bunt, often conducting polemics and debates representing the artistic and ideological between those groups.

Formism is approaching

In 1919, the group adopted a new name, which was employed for the first time on the occasion of the its exhibition in April of that year in Warsaw, and was later applied to the entire period of the group’s activity, since 1917, maintaining different markers of continuity, e.g. in the numeration of collective shows. The change, preceded by heated discussions within the group, was motivated by a need to cut off from Expressionism, due to, for example, its connection to the German tradition and culture. In this way, the Kraków artists also stressed their separation from the Poznań art clique.

During that period, the leading theoreticians of Formism were Tytus Czyżewski and Leon Chwistek, as well as his antagonist – Witkacy. As Chwistek wrote, Formism’s biggest aspect was a revision of the problem of form and content in art, as well as solidification of the superiority of the former. In his words, artists liberated themselves from the external reality and began spontaneously creating their own. Leon Chwistek was a supporter of aesthetic pluralism, which was reflected in his concept of multiplicity of realities, which found their counterparts in different painting types. Fascinated with Futurism, he developed the original concept of Spherism in painting. Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, on the other hand, held the opposite position and formulated a theory of unity of reality. Nonetheless, he agreed with Chwistek in regarding the independence of an artist as one of the central conditions of art. He also introduced several notions, which were important to his aesthetic concepts, and at the same time characterised Formism, such as for example Pure Form, ‘insatiability of form’ or ‘directional tensions.’

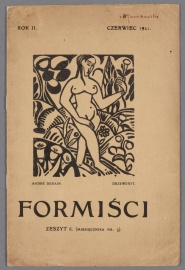

Formists were an incredibly active formation, as they not only organised a score of exhibitions, often in collaboration with other groups, but also numerous lectures, poetry and drama meetings, propaganda actions – so called ‘Formist mornings,’ which earned them supporters, also among artists from abroad, such as Gustaw Gwozdecki, Eugeniusz Zak, and Ludwik Markus. Their only exhibition abroad, which took place in 1922 in Paris, received positive reviews from the local critics. Formists gained prominence and fame in other art circles in Poland, and some of them even established branches of the group of sorts. The Warsaw group of Formists gathered: Mieczysław Szczuka, Wacław Wąsowicz, Kamil Romuald Witkowski, and Jerzy Zaruba, while in Lviv they included: Ludwik Lille, Stanisław Matusiak, Zygmunt Radnicki, and Zofia Vorzimmer. They also likely owed their success to the Formiści journal published in Kraków since October 1919 until June 1921. It was edited by Tytus Czyżewski and Leon Chwistek, who was succeeded by Konrad Winkler in 1921. Apart from texts on art, the magazine also published works by the Formists – mainly drawings.

By 1922, the group of Formists had practically ceased to exist, both in Kraków and in the Warsaw branches. This was caused by growing differences in views among the artists, who strongly manifested their radical positions. Members of the group were also involved in other movements, most commonly Colourism and Constructivism. In 1927 an attempt was made in Warsaw to reactivate the movement by organising an exhibition at Zachęta with works by artists from the capital, including: Tytus Czyżewski, Andrzej Pronaszko, Szymon Rutkowski, Konrad Winkler, Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Romuald Kamil Witkowski, and Jerzy Zaruba, however, despite counting over ninety paintings, it failed to achieve its intended goal.

Before the outbreak of the war, in 1938, the first attempt was made to assess the movement’s achievements, in a special issue of Głosy Plastyków. At the same time, the Museum of History and Art launched an exhibition with a permanent section devoted to Formism.

Author: Magdalena Wróblewska, ed. TS, transl. AM, May 2017

Bibliography

- Iwona Luba, Dialog nowoczesności z tradycją. Malarstwo polskie dwudziestolecia międzywojennego, Warsaw, 2004

- Joanna Pollakówna, Formiści, Wrocław, 1972

- Formiści, exhibition catalogue edited by Irena Jakimowicz, National Museum in Warsaw, 1989

No Comments