19 Apr The Shame of Shaving Hair: Female Punishment Across History

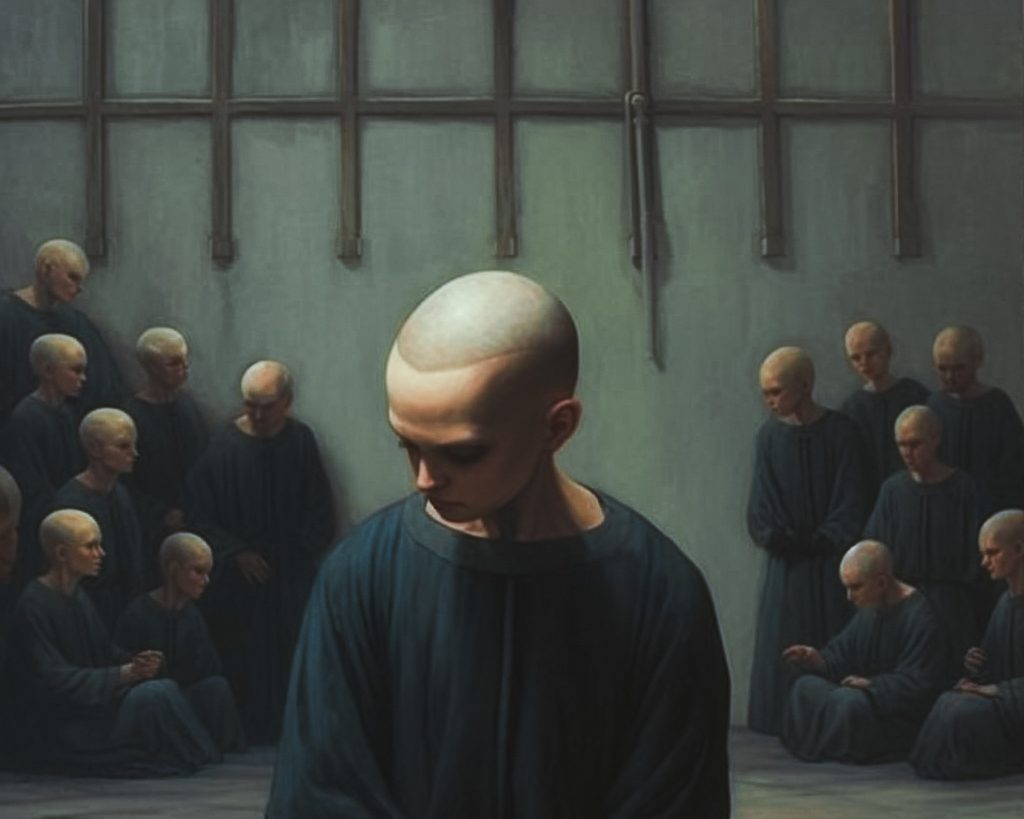

Hair, serving as an extension of selfhood, carries profound symbolic weight across cultures. Regarded as an integral facet of identity, femininity, and status, hair becomes an object of intricate interplay between personal and societal constructs (Synnott, 1987). The manipulation and removal of hair, in particular, constitutes a striking expression of power dynamics, often employed as a tool for humiliation, punishment, and control. As this embodiment of the personal meets the political, hair emerges as a battleground of conflicts and discourses that resonate deeply in cultural history.

The coercive removal of women’s hair, more specifically, offers a lens into the systemic subjugation and control of women across epochs. Shaving, as an act that symbolically and physically alters a woman’s identity, signifies a forcible imposition of societal control over her body. This practise carries an inherent disempowerment, severing not only the hair but also one’s ties to selfhood and the society at large (Weitz, 2001). As such, hair shaving becomes a potent form of punishment, imbued with symbolic violence that extends far beyond its physical enactment.

This article undertakes an exploration of hair shaving as a punitive measure, tracing its manifestation from the realms of Ancient Rome through the tumultuous events of the 20th century. In reviewing these instances, the aim is not only to illuminate this form of female punishment but also to highlight the enduring presence of gendered power dynamics that cut across different cultures and periods.

Throughout this journey across time, one discerns a recurrent narrative: the policing of women’s bodies and identities, the enforcement of societal norms, and the perpetuation of power imbalances. Hair, in its dual role as a personal and societal symbol, forms the canvas upon which these dynamics play out. By examining the practise of hair shaving as punishment, we gain valuable insights into the depths of societal control over women, the contours of resistance, and the evolving discourses on femininity and power.

In Ancient Rome, hair was imbued with profound cultural and social significance. A woman’s hair, maintained long and uncut, served as a prominent marker of honour, respectability, and societal standing (Treggiari, 1991). It formed an essential aspect of a woman’s public persona, often signifying her chastity, virtue, and fidelity. Hair also held a crucial role in marital rites, where it was intricately arranged to signify the transition of a girl to a matron. Thus, within the fabric of Roman society, hair emerged as a critical component of a woman’s identity and societal position.

Against this backdrop, the manipulation of hair assumed a potent role in the public disgrace and punishment of women. A clear instance of this was observed in the treatment of women found guilty of adultery. Such women were subjected to the ignominy of hair shaving or cutting, a punitive measure intended to publicly shame and disgrace them. The removal of their hair was a symbolic act, serving as a visual representation of their alleged moral lapse (Treggiari, 1991).

This punishment, however, was far from merely physical. It bore the weight of symbolic violence, working to demean and strip these women of their societal status and respectability. The shorn hair served as a visible marker of their disgrace, alienating them from societal norms of honour and virtue. In essence, the act of hair cutting extended beyond the physical, engendering a profound alteration of the woman’s societal image and identity.

Furthermore, this form of punishment functioned as a societal mechanism of control and regulation. By enforcing strict moral codes through such visible and symbolic punishment, Roman society sought to maintain the established order and control female behaviour. Hair, in this context, was both a tool and a site of societal control, offering a stark illustration of the power dynamics that shaped Roman society (Treggiari, 1991).

The Medieval and Early Modern periods in Europe bore witness to a grim chapter in the history of women’s hair – the witch trials. This was an era dominated by intense religious piety, superstition, and a pervasive fear of the devil and witchcraft. During the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly, thousands of women across Europe, including Poland and other Slavic regions, were accused of witchcraft, leading to large-scale witch hunts and trials (Gibbons, 2013; Sullivan, 1997).

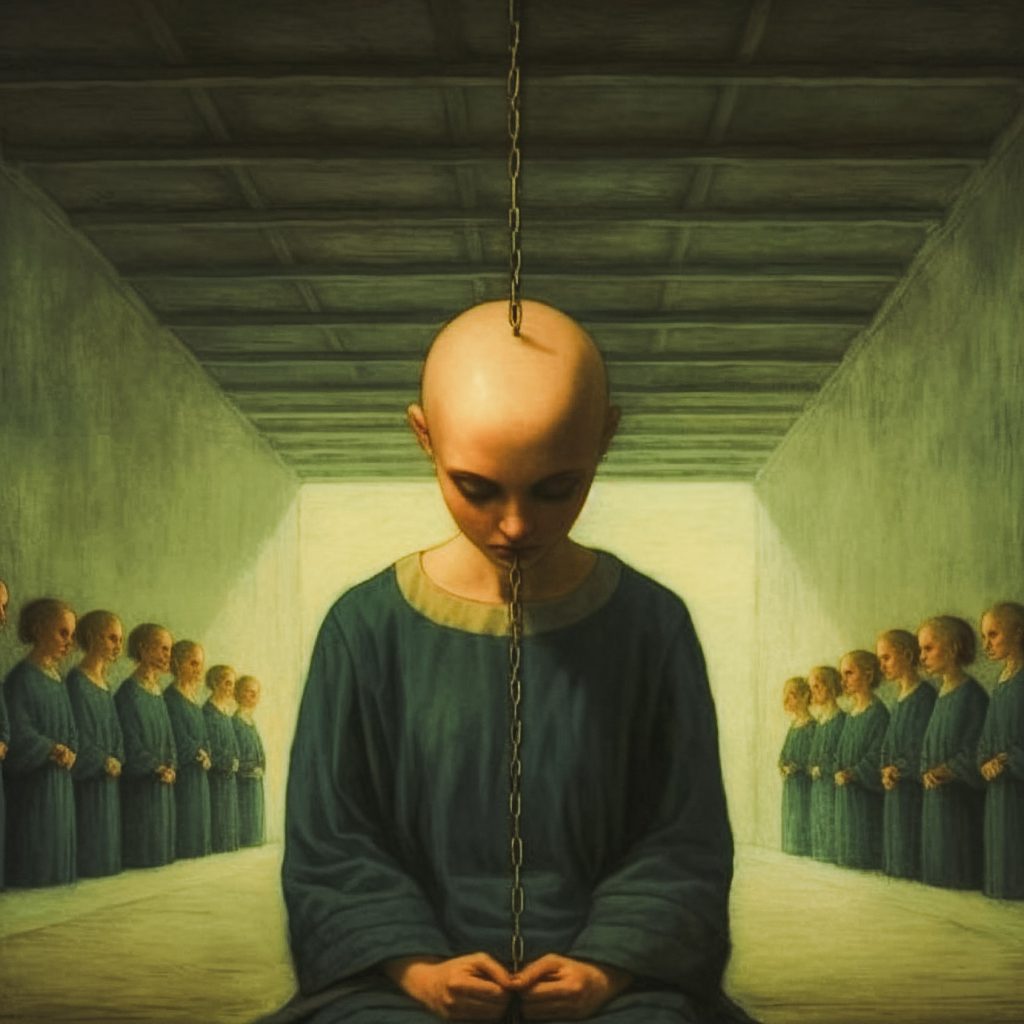

In the midst of these witch trials, hair shaving emerged as a salient punitive practice. Women accused of witchcraft were routinely subjected to head shaving. This practice was rooted in the prevailing belief that the Devil, or demonic forces, could conceal themselves within a woman’s hair. Shaving the woman’s head was thus perceived as a form of exorcism, a means to physically expose and expel the concealed evil (Sullivan, 1997).

However, the implications of hair shaving extended well beyond its alleged spiritual rationale. It served as a powerful instrument of public disgrace and social humiliation. The shorn head of the accused woman stood as a stark, visible sign of her alleged witchcraft, marking her as an outcast and subjecting her to public scorn. This physical marking mirrored the societal marking of these women as deviant and dangerous, further alienating them from the community (Gibbons, 2013).

Additionally, the shaving of hair constituted a de-feminising act. As hair was widely regarded as a symbol of femininity and beauty, its removal worked to strip the accused women of these attributes. In effect, it worked to dehumanise them, reinforcing their portrayal as demonic entities and further legitimising their punishment (Sullivan, 1997).

The practice of hair shaving during the witch trials, thus, embodies the complex interplay between societal beliefs, power dynamics, and gender norms. Serving as a potent form of social control, it illustrates how hair – and its manipulation – was instrumentalised to uphold societal norms, regulate women’s bodies and behaviours, and negotiate power relations within the society.

The early 20th century in Ireland was marked by a period of significant turmoil and conflict, with the Irish War of Independence (1919-1921) and the subsequent Civil War (1922-1923). Within this fraught historical backdrop, the practice of hair shaving resurfaced as a mechanism of punishment and control (Ryan, 2002).

The targets of this punitive measure were primarily women accused of fraternising with or offering succour to British soldiers. Labelled as ‘traitors’ or ‘collaborators’, these women were perceived as betraying the Irish nationalist cause. Their perceived acts of betrayal ranged from personal relationships with British soldiers to providing them with meals, lodging, or information. In a climate of war and heightened nationalism, such actions were seen as a significant threat, and these women were often subjected to public humiliation and punishment (Ryan, 2002).

Hair shaving was a prevalent form of this public humiliation. Women accused of fraternising with British soldiers were forcibly shorn of their hair, often in public and amid substantial communal participation. The removal of hair served as a potent symbolic act, transforming these women into visible markers of ‘treason’. Their shaven heads stood as physical testimonies to their alleged acts of betrayal, marking them out for public shame and ridicule (Ryan, 2002).

Beyond the immediate humiliation and stigmatisation, the practice of hair shaving had far-reaching implications. It effectively isolated these women from their communities, making them the subjects of scorn and alienation. The public nature of this punishment further served as a deterrent for others, reinforcing the boundaries of acceptable behaviour and allegiance amidst the struggle for independence (Ryan, 2002).

Moreover, this practice reflects the complex interplay of gender, power, and nationalism during this period. It underscores the way women’s bodies and appearances were manipulated and controlled as part of wider political and nationalistic conflicts.

During the upheaval of World War II, the historical punitive practice of hair shaving was once again employed, this time targeting women accused of collaborating with the Nazis. This grim practice took place across various occupied territories, notably in France, Poland, and other parts of Europe (Ross, 2012; Virgili, 2002).

Women who were seen to have collaborated with the enemy, whether through relationships with Nazi soldiers or other forms of assistance, were denounced as ‘collaborators’ or ‘horizontal collaborators’. These labels marked them as traitors, as women who had betrayed their nation and their people by aiding the occupying force. Their alleged acts of collaboration, thus, invoked significant moral outrage, leading to their ostracisation and punishment (Virgili, 2002).

Hair shaving emerged as a prevalent form of this punishment. Accused women were forcibly shorn of their hair, often in public spaces and amid large gatherings. This public spectacle served to maximise the humiliation and disgrace experienced by these women. The sight of their shaven heads stood as a stark visual symbol of their alleged treachery, rendering them objects of public shame and scorn (Ross, 2012).

The significance of this practice extended well beyond the immediate humiliation. It effectively marked these women as social pariahs, isolating them from their communities and reinforcing their status as traitors. Moreover, the very public nature of this punishment served to consolidate community solidarity against the perceived enemy and to deter others from engaging in similar acts of ‘collaboration’ (Virgili, 2002).

Reflecting on this practice, one finds echoes of earlier historical instances, underscoring the enduring power of hair as a symbolic and sociocultural tool. It highlights the recurrent manipulation of women’s hair as a vehicle for exercising societal control, expressing moral outrage, and negotiating power relations within a community. The specific context of World War II further underscores how these practices can be harnessed as part of larger political and militaristic conflicts, with women’s bodies serving as battlegrounds for these struggles (Ross, 2012).

In the latter half of the 20th century, this form of punishment persisted. During the Vietnam War, women suspected of collaboration faced the brutality of hair shaving by the Viet Cong (Schwenkel, 2006). The Rwandan genocide bore witness to a horrific twist on the practice, as Tutsi women were forcibly shaved by Hutu captors, erasing their identities and deepening their humiliation (Hatzfeld, 2007).

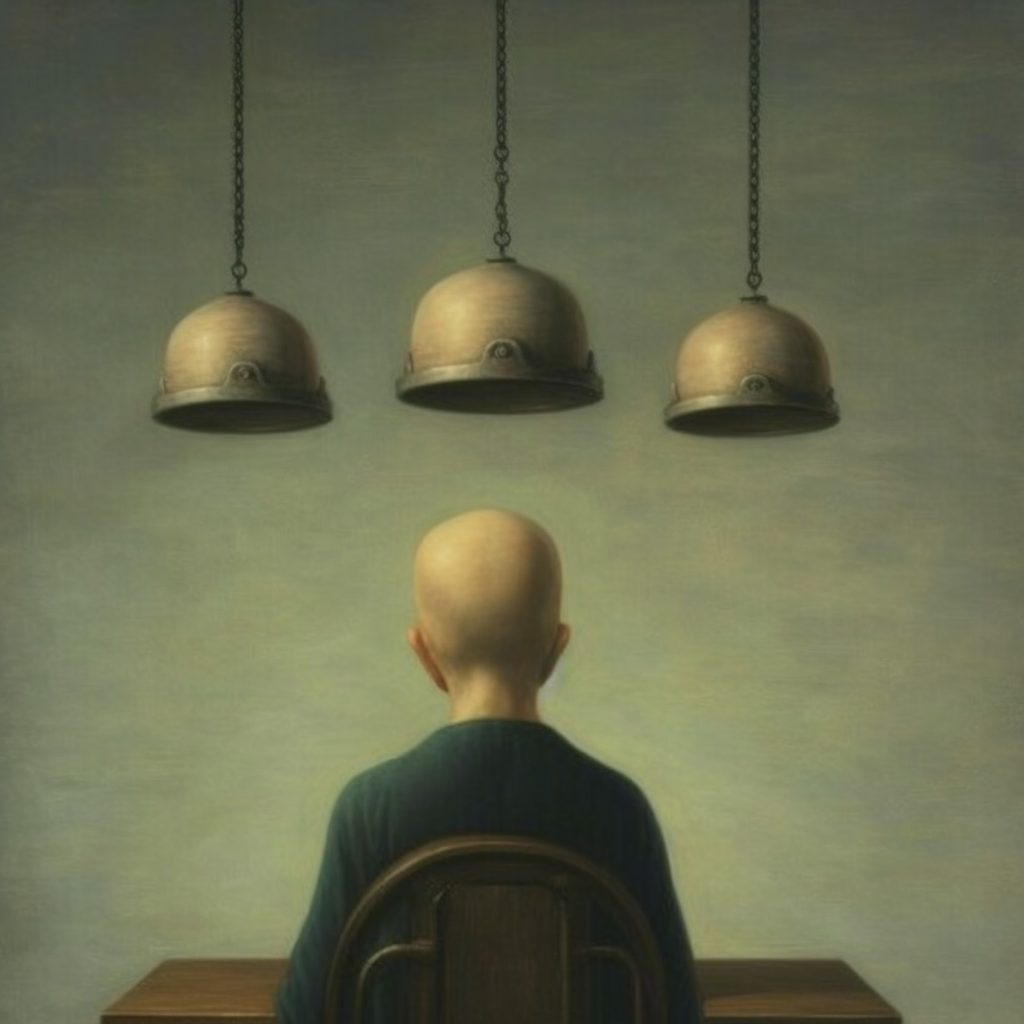

In concluding, the act of shaving a woman’s hair as a punitive measure provides a stark illustration of the potent symbolism of hair in societal norms and values. Hair, far more than a mere biological feature, occupies a significant place in the sociocultural tapestry, holding a plethora of meanings and connotations across various cultural and historical contexts. It is intertwined with notions of identity, femininity, honour, and status, with its manipulation serving as a powerful tool for societal control, moral judgement, and enforcement of societal norms.

Why, then, has hair been targeted in instances of public shame and punishment? The answer lies in its symbolic richness and visibility. As a prominent, physical feature, the alteration or removal of hair provides a tangible, visible sign of a woman’s supposed transgression. It serves as a public declaration of her disgrace, making her a subject of collective scrutiny and judgement.

Moreover, the removal of hair can be seen as a symbolic act of stripping away a woman’s femininity and dignity, reducing her to a state of vulnerability and shame. This action, in effect, devalues and dehumanises the woman, reducing her to her supposed ‘crime’ or ‘sin’. This process, performed publicly, seeks to reassert societal control and reinforce societal norms and values, effectively using the woman’s body as a canvas upon which these norms and values are inscribed.

In this sense, the practice of hair shaving serves as a microcosm of larger societal structures and attitudes, particularly those pertaining to gender and power. It reflects the systemic ways in which women’s bodies have been controlled, regulated, and subjugated throughout history, and the ways in which this control is enacted and reinforced through bodily practices and rituals.

Therefore, the historical instances of hair shaving as a punitive measure serve as a poignant reminder of the powerful interplay between the body, society, and culture, and the enduring significance of hair in this intricate relationship.

References

Gibbons, J., 2013. Witchcraft and Women: A Historiography of Witchcraft as Gender History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hatzfeld, J., 2007. Life Laid Bare: The Survivors in Rwanda Speak. New York: Other Press.

Ross, J., 2012. ‘Shorn Women: Gender and Punishment in Liberation France’. In Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 22, pp. 227-246.

Ryan, L., 2002. ‘Furies and Diehards: Women and Irish Republicanism in the Early Twentieth Century’. In Gender & History, 14(2), pp. 290-308.

Schwenkel, C., 2006. ‘Recombinant History: Transnational Practices of Memory and Knowledge Production in Contemporary Vietnam’. In Cultural Anthropology, 21(1), pp. 3-30.

Sullivan, M., 1997. ‘The Witches of Dürer and Hans Baldung Grien’. In Renaissance Quarterly, 50(2), pp. 432-452.

Synnott, A., 1987. *Shame and Glory: A Sociology of Hair*. British Journal of Sociology, 38(3), pp.381-413.

Treggiari, S., 1991. Roman Marriage: Iusti Coniuges from the Time of Cicero to the Time of Ulpian. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Virgili, F., 2002. ‘Women in Wartime: The Shaving of Women’s Heads as a Marker of Difference’. In Clio: Women, Gender, History, 16, pp. 111-122.

No Comments