31 Oct Guillermo del toro: AT HOME WITH MONSTERS

Guillermo del Toro (b. 1964) is one of the most inventive filmmakers of his generation. Beginning with Cronos (1993) and continuing throughThe Devil’s Backbone (2001), Hellboy (2004),Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), Pacific Rim (2013), and Crimson Peak (2015), among many other film, television, and book projects, del Toro has reinvented the genres of horror, fantasy and science fiction. Working with a team of craftsmen, artists, and actors—and referencing a wide range of cinematic, pop-culture, and art-historical sources—del Toro recreates the lucid dreams he experienced as a child in Guadalajara, Mexico. He now works internationally with a cherished home base he calls “Bleak House” in the suburbs of Los Angeles.

“To find beauty in the profane. To elevate the banal. To be moved by genre. These things are vital for my storytelling,” says Guillermo del Toro. “This exhibition presents a small fraction of the things that have moved me, inspired me, and consoled me as I transit through life.”

A unique exhibition organised by the Art Gallery of Ontario, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Minneapolis Institute of Art explores the creative mind behind one of the most inventive filmmakers of our generation revealing his influences, from the Medieval era to contemporary culture, and his particular obsession with horror, fantasy and the rich heritage of the Victorian era. At Home with Monsters is organized thematically, beginning with visions of childhood and innocence and the Victorian era; continuing through explorations of death and the afterlife, magic, occultism, alchemy, Frankenstein and horror, monsters; and concluding with a celebration of comics, movies and popular culture.

“Guillermo del Toro believes that we need monsters,” says Jim Shedden, co-curator of the exhibition and the AGO’s Manager of Publishing. “To him, the imperfections of monsters are found in all of us, whether we see them or not. At the same time, despite his empathy for the tragic monster, del Toro is fascinated with truly terrifying and invulnerable monsters. By witnessing his incredible creative process, we can make unexpected connections among different genres and narratives, high art and pop culture, and blur boundaries between fantasy and reality.”

Ever since his first film – Cronos (1993) Guillermo del Toro signature has been a vivid use of color. With a particular choice of for steel blues, blood reds, and sepia yellows, his moviemaking is not just aesthetically rich, but representative of the full thematic potential of color.

Pan’s Labyrinth is a perfect example of that. Whenever the film’s protagonist, Ofelia (Ivana Baquero), moves between the post-Spanish Civil War world she lives in and the fairytale world she escapes to, the color palette shifts. The “real” world is often cold and blue, and the other world is warm with crimsons and yellows — as seen in this shot where Ofelia enters a fantasy throne room. On the one hand, it provides a visual cue to let us keep track of which world we’re in. On the other hand, it reflects its nature: gentle, warm, and promising of safety that Ofelia can’t find elsewhere.

Guillermo del Toro movies utilize a rarely used color scheme known as “Triadic” to create these impossible worlds. ( A triadic color scheme is when three colors that are evenly spaced around the complementary color wheel are used in conjunction. One color in the triadic colors scheme is chosen to be the dominant one with other two used in complementary fashion. Triadic color schemes are somewhat less common because they can look a bit cartoonish).

Del Toro’s genius lies in how he balances these colors so that they never seem overwhelming and always keep one foot in reality.

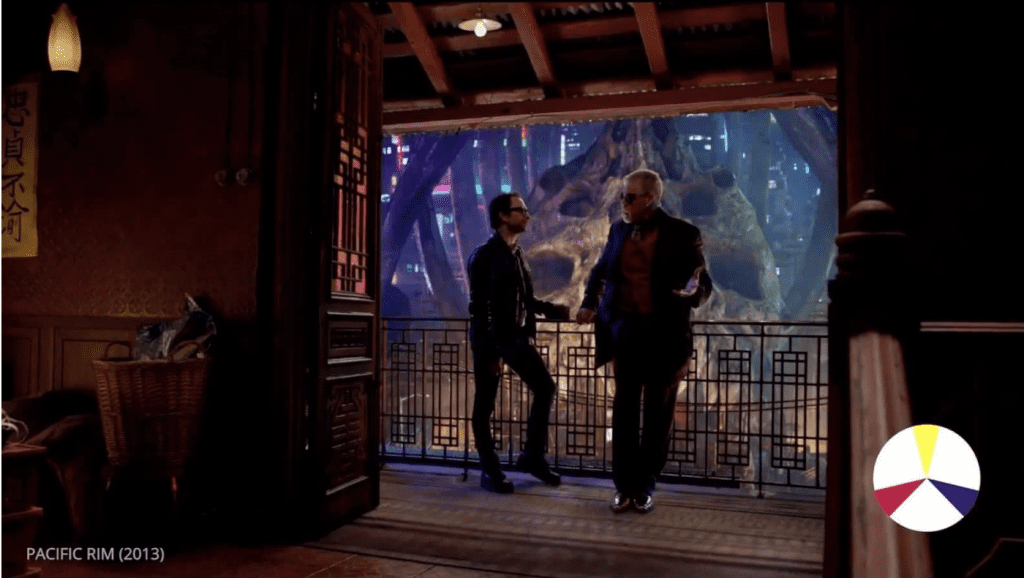

Take Pacific Rim as an example. Pacific Rim, ostentatiously, takes place in our near future. Things haven’t changed too much. People still generally dress the same. Countries and jobs feel familiar. Except, of course, the fact that this is a world where giant fighting robots regularly slug it out with giant kaiju monsters in hand-to-hand combat.

In the hands of del Toro, colors can not only reflect a place, but also a character’s place in it. Take this moment in The Shape of Water where Elisa (Sally Hawkins) and Zelda (Octavia Spencer) are cleaning a men’s bathroom in the secret government facility they work in.

Given their profession as cleaners, men like Strickland (Michael Shannon) can be prone to seeing them as almost invisible – simply background noise in human form. Del Toro cleverly symbolizes that by choosing a hue for Elisa and Zelda’s uniforms that matches the bathroom’s color scheme and makes them almost disappear into it.

Del Toro has said that “color should tell you about the character,” and his films demonstrate that philosophy at work. A good example is a scene in Crimson Peak where Edith (Mia Wasikowska) wears a golden dress while exploring the depths of the gothic home in which she finds herself. He uses Edith’s dress to reflect who she is: kind, good, and even wealthy. The director also boosts that color-driven representation by juxtaposing the dress with the blood-red of the vats that Edith is investigating. Not only does the red make the gold dress pop more on the screen, but it also provides an added story effect: it makes Edith seem all the more vulnerable and threatened by the ominous substance beneath her.

Edith’s innocence is perpetually threatened throughout Crimson Peak, but is arguably not fully lost until the film’s final confrontation. Given that white is a widely recognized symbol of innocence, it’s no accident that del Toro puts Edith in that color here as evil descends on her. But the director also accentuates how the character is losing her innocence by providing the stark contrast of the blood red on her hands. That whole journey is conveyed using nothing more than one piece of clothing and shrewd use of color.

Red as a life and death symbol.

Guillermo uses colour red in a very particular way. Like all other colours he uses, it has a deeper meaning to it, we can see that clearly in a single scene from The Shape of Water where in this particular moment where he captures both meanings in a single shot. Death comes in the form of the Amphibian Man’s bloody handprint on a movie theater poster, while life is found in the red wall of the ticket booth — since, for the director, cinema is life, as it is for Elisa, who lives above the theater in this shot. In that way, del Toro has introduced a charming bit of character and director symmetry here – each sharing a perception of a ticket booth as the gateway to the passion that makes them feel, respectively, alive. His color uses don’t always appear to be quite so personal, but in this case, it’s a pleasant reminder not just of his passion for movies but, in a way, our own, too.

No Comments